Davena Zhang

Our knowledge of the refugee crisis began in 2015 with the alarmingly rapid flow of refugee travel from Middle East to neighbouring areas in Europe. For the migrants from Syria, the on going Syrian war has left them without a permanent home for several years now. In July 2015, the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights (UNHCR) declared the Syrian refugee crisis the largest refugee population in a generation. Since the start of 2016, over 90,000 of their sea journeys to countries like Greece or Italy have been successful, to say nothing of the arrivals on land. Neither route is safe —both expose the refugees to harsh weather conditions that threaten dehydration, contraction of disease, hunger, as well as violence at foreign borders. The EU promise of free borders and welfare has attracted those who seek alleviation of the “abject poverty” in Syria as well as the threat of persecution and violence in Afghanistan.

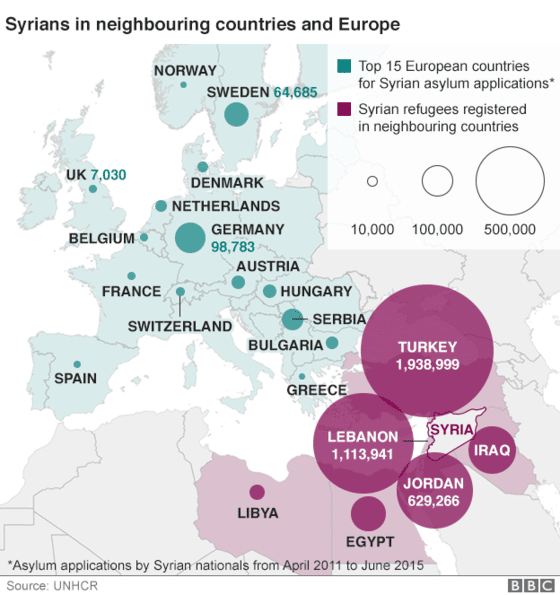

Sweden and Denmark have recently pushed for tighter border controls, complicating the already drastically uneven distribution of refugees. The UK has promised to resettle 20,000 ‘vulnerable’ people, but as of June 2015 barely housed half that number (Fig. 1). As of March 2015, Turkey has already seen an influx of more than 1.7 million (UNHCR 2015). Strong cultural differences also have a part to play in the debate on granting asylum to refugees. For example, the sexual assaults and muggings on New Year’s Eve in Cologne have been attributed to the cultural views of North African migrants and have been the platform on which Germany begins its acceptance of asylum seekers. Though refugee and migrant crimes form serious grounds for concern, this cannot serve as a focal point for the rejection of the wider demographic of refugees and cannot justify the spread of xenophobia or hate. This is already evident with the increasing arson attacks on refugee shelters.

Number of refugees in Syria’s neighbors and Europe (UNHCR and BBC 2015).

Amidst the tangle of politics and polemics are the imminent health effects of this staggering displacement of people in Europe. Three in ten Syrian refugee families living in Jordan cannot afford access to health care (Shabeeb 2015). Ironically, this strikes a parallel with the disintegration of Syria’s own health care system. Ninety-five percent of doctors in Aleppo have left, died or been detained (Physicians for Humans Rights 2015). The flow of resources has decimated the Syrian healthcare system, which was once lauded as one of the best in the region. In their host nations, refugees still face lack of vaccinations and management of chronic illnesses, risk of malnutrition, and risk of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). According to UNICEF, one third of Syrian children were born during the war, meaning that these millions of children have had their education interrupted or forestalled and have not had a safe and stable home. A study conducted with Syrian refugee children showed that almost half suffer from PTSD, with girls at double the risk for depression (Sirin and Rogers-Sirin 2015). Reports have also indicated high levels of sexual and gender-based violence among Syrian women in Jordan, as women are forced into prostitution or child marriage to pay for food or rent (Anani 2013). Women have also been harassed by illegal smugglers and fellow refugees on their journey, and often remain silent to avoid delays in their transit. Some go as far as avoiding food or water so that they do not have to use the shared-gender bathrooms, according to Amnesty International. Cultural and language barriers exacerbate the isolation of these refugees and indicate the desperate need for specialised care. Host countries are only beginning to grapple with these issues, by mobilising experts that deal with mental health issues in refugee camps (Melville 2015). In 2014, the Turkish government lifted legal barriers for refugee access to education and accredited temporary education centers with an Arabic curriculum, but this effort has been hindered by overcrowding, which forces most refugees to live outside refugee camps (Human Rights Watch 2015). UNHCR refugee camps fail to encompass displaced individuals who live outside the camps in deserted buildings, without access to humanitarian aid (Mailman School of Public Health 2015).

Even more worrying is the lack of control of communicable diseases. While the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London asserts that “there is no systematic association between refugee migration and the importation of infectious diseases,” it has been clear that there is a serious risk of diseases spreading. According to public health researcher Doctor Adam Coutts, the war in Syria disrupted a vaccination program against measles, which had spread to 7000 people. Denmark, which has not seen a case of diphtheria in twenty years, has warned of a possible outbreak as the disease was found in two Libyan refugees. Cutaneous leishmaniasis, a vector-borne disease, is endemic to much of the Syrian population due to malnutrition and poor housing conditions. Lebanon had not seen a single case of the disease before 2008, but in 2013, 1033 incidents of leishmaniasis were confirmed, 96.6% of which were among Syrian refugees (Sharara and Kanj 2014). To address the urgent concern of the spread of communicable diseases, Germany has mandated health assessments for refugees upon arrival including tests for tuberculosis, which was of high incidence in Syrian refugees (Cookson 2015). Yet such practices place a huge amount of stress on governments to care for masses of people in a timely manner and have faced backlash from the public. As such, European leaders like Angela Merkel find themselves in the precarious balancing act of enforcing their border policies while quelling anxieties about increasing populations of refugees. Yet, restricting access to healthcare cannot and should not be the solution to this large demand for physical and psychological attention. In fact, a study by Bozorgmehr and Razum in 2015 showed that Germany’s restriction of healthcare for refugees actually led to increases in both delay and costs of care. Instead, greater efforts to upscale medical aid to refugees are needed to ensure the wellbeing of refugees, citizens and humanitarian workers.

Three refugees arrive the island of Lesbos, Greece (UNICEF 2015).

Host nations like Jordan have increasingly relied on organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières and the UNCHR, as well as emerging humanitarian groups in the Middle East, to aid in the management of this crisis. Jennifer Leaning, assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, has pointed out that these organizations are also scrambling to meet demand, and have to “play catch up with catastrophe that has been allowed to get out of control somewhere” (Schachter et al. 2015). There is neither government-based infrastructure in place to deal with the large influx into their countries, nor is there a protocol to intervene in the early stages of conflict to prepare or prevent massive displacement of people. In the same vein, Dr. Neil Boothby, professor at Columbia Medical Center, asserts the importance of long-term goals in managing the refugee crisis as a whole (Mailman School of Public Health 2015). Without a clear end to conflict or the boosting of regional economies, these displaced people will find difficulty in securing their futures. The Syrian refugee crisis is but one of the many streams through which people have been displaced. Each refugee crisis is different and needs to be regarded in its own context and needs. However, we need a system that is more globalised, more sensitive, and more forward-looking to deal with the allocation of resources in these crises.

Refugees in Za’atri, Jordan, wait or relief items (UN News Centre 2012)

We need to bridge the disconnect between the various factions dealing with the refugee crisis – humanitarian workers, healthcare professionals, and governments alike. Ultimately, we must take collective responsibility for the safety and wellbeing of both refugees and citizens. This must involve specialized and culturally-appropriate medical care. As children are at their most plastic stage of development, particular attention must be raised about their psychological and educational support. Finally, access to medical attention is unfeasible without proper economic aid, which is seriously needed for safe and accessible housing for these refugees. The fact that the United Nations received only 37% of funds needed to support Syrian refugees in 2015 shows the importance of collective action in affecting many lives (Barakat and Zyck 2015). Until we can find a solution altogether, the discourse on the Syrian refugee crisis and many similar aid crises will be shrouded by unproductive and isolationist arguments.