Elad Mashiach

Rare diseases are diseases that are the least prevalent and most difficult to treat. Yet, these pique the most interest from the scientific community. The treatments in this large group of diverse, complex diseases have little to no similarities. Thus, these diseases cannot be grouped under one umbrella, and therefore are typically coined “orphan diseases.” Clark informs us that in the U.S., an orphan disease is defined as a rare disease that affects fewer than 200,000 people. Scientists have discovered approximately 7,000 rare diseases, and nearly half of these affect fewer than 25,000 people (Clark 1). However, they collectively affect nearly 25 million people in the U.S. (Reuters 3). The collective term “diseases” is misleading because the conditions collectively affect a total of 350 million people worldwide, meaning that 1 out of 17 people will develop a rare disease in their life (Ehinger 2015). Since the prevalence of these diseases is so low, the medical community and pharmaceutical companies have paid them limited attention in comparison to more prevalent diseases such as cancer and cardiac diseases. In fact, pharmaceutical industries are especially limited in knowledge regarding developing research and development (R&D) of drugs. An exploration of how orphan diseases affect the patients, the pharmaceutical industry, and government regulation shows that more attention, research, and resources need to be drawn for treatment and possible cure of some of these orphan diseases.

Patients affected by orphan diseases receive little insurance coverage and aid from both the government and the private sector. These patients battle some of the most chronic diseases including Multiple Sclerosis and Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. Such diseases cause paralysis and muscle deterioration, leading to a poor quality of life for those affected. These patients often have to go to specialized tertiary care hospitals for diagnosis and treatment, and use off-label drugs to treat the condition. For example, in order to maintain muscle movement and delay deterioration, patients with Multiple Sclerosis often succumb to using drugs that are very similar to the anabolic steroids used by bodybuilders. These steroids are nonspecific to the muscles affected by Multiple Sclerosis and therefore carry side effects. Patients also face the obstacle of having a limited variety of available drugs to take. Those with diseases like AIDS and cancer may take cocktail drugs, which is a combination of different drugs that collectively help fight the disease and reduce symptoms. If a patient is allergic to a particular drug, or if there is an interference between two drugs, then that patient can take a replacement drug that can induce the same effects. This is not the case for patients with orphan diseases, however, because they have very few drug options (Reuters 4). Dr. Alan Schlechter, a renowned child and adolescent psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital explains to us that when a doctor treats a patient, the focus of treatment is on that patient specifically, regardless of the prevalence of the disease. However, Dr. Schlechter notes that understanding certain orphan diseases like Epidermolysis Bullosa (a rare genetic skin disease) can advance our knowledge of a whole group of skin diseases known as Cutis Laxa.

Orphan illnesses are not solely about providing the right medication, but rather about providing the right treatment. Dr. Schlechter notes that in psychiatry, substance abuse is often seen as the classic orphan illness for the lack of available treatment. For instance, Dr. Schlechter explains, “we know a lot about drug abuse. For example, for a heroin addict it takes a full year for the receptors in the brain to fully return to normal. Now imagine being told that for a full year you are not going to feel good. If we put the money into this year-long treatment, it is clearly beneficial.” For that specific reason, Dr. Schlechter decided to also help substance abuse patients in the LGBT youth community, which was rarely ever done before.

We are often oblivious to the extent of the pivotal role that the pharmaceutical industry plays in the treatment of diseases. Nowadays, it is not feasible for the government to fund research, drug development, and clinical trial execution for diseases worldwide. Therefore, the private pharmaceutical industry arose to combat this unmet need. On one hand, pharmaceutical companies annually invest millions, if not billions, of dollars to combat and develop treatment for numerous prevalent diseases including cancer and Alzheimer’s. However, on the other hand, the picture is not as bright with orphan diseases. The small patient pool coupled with the diversity between these diseases provides little financial incentive for the private sector to create and market new medications for treatment or prevention. Dr. Schlechter explains that the shift of attention toward orphan diseases from pharmaceutical companies will only happen if as a society we decide to subsidize it like we do, for instance, for agriculture. Fortunately, in recent years this paradigm has started to shift toward more investments in orphan drug development (Tzeng 2014).

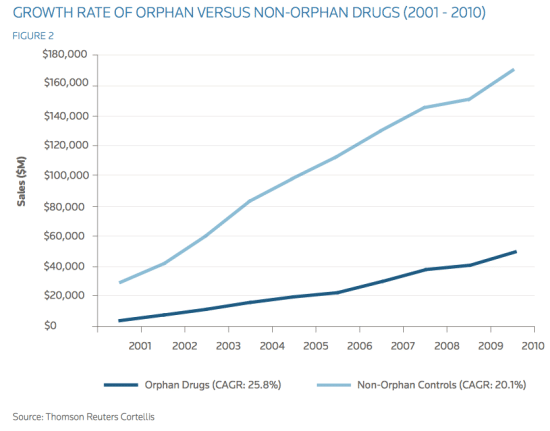

Fig. 1. The growth of orphan drugs when compared to non-orphan drugs

The establishment of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983 with the help of the government, publicly gave medical attention to orphan diseases for the first time. This act encouraged development of orphan drugs, and together with high-profile philanthropic funding at the time, attention toward orphan diseases grew vastly. In the decade before the Orphan Drug Act, only ten drugs for orphan diseases were in the market, but after the act was passed, over four hundred new drugs have been approved by the FDA (Clark 1). This progress is enormous, but when compared to the resources and time devoted to developing drugs for common diseases, it is minuscule. Although orphan drugs are significantly diverse, they target a small patient population and are extremely expensive to develop. Pharmaceutical companies, however, should direct their attention to expanding orphan drug development based on three common factors to all orphan diseases.

First, the orphan conditions of interest to pharmaceutical companies are chronic or degenerative in nature and lead to a poor quality of life and/or shortened lifespans. That is to say, these are conditions that generate an extremely high need among patients to receive effective treatment. Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, for example, leads to progressive muscle deterioration and paralysis in 1 out of 3,500 boys, resulting in an average life span of less than 30 years (Tzeng 2014). This should be especially appealing to pharmaceutical companies because it results in patient dependence on the drug for a longer time than an acute disease does.

Another factor that should prompt pharmaceutical companies to implement orphan drug development is the notion that effective orphan drugs have been historically rewarded with exceptionally high prices. Such an example can be seen with the marketing of the drugs for Genzyme’s Cederase for Gaucher in 1992, when the annual price tag per patient was approximately $200,000 (Tzeng 2014). Among the drugs that have been developed, most have been supported by a targeted commercial footprint that helped cut down the cost. For example, Aegerion’s Juxtapid drug for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia is being supported by approximately twenty-five sales representatives that focus on key specialists (Tzeng 2014). A marketing strategy like this that involves sales representatives helps to compensate for the expansive R&D cost of the drug.

It is no secret that pharmaceutical companies’ decisions are majorly motivated by

financial profit. As shown above, not only does the financial benefit from orphan drugs exceed that of more common diseases, but it also allows cut of production cost and maintains exclusive rights for a longer period of time. Furthermore, with the current stagnation in traditional pharmaceutical markets, companies should very soon feel the pressure to turn to developing orphan drugs. As seen in Figure 1, while orphan drugs make up only approximately six percent of total pharmaceutical sales, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of orphan drugs between 2001 and 2010 was an impressive 25.8 percent. In comparison, 20.1 percent was the growth of control, non-orphan drug sales (Reuters 6). Projection of this data into the future suggests that orphan drugs will be in high demand among the affected patients and will outshine the sales of non-orphan drugs over the next 30 years. Lastly, when looking at orphan diseases from a regulation standpoint, we can foresee a positive future for orphan drug development. Government incentive to enforce orphan drug development can help to catalyze the process. In the United States, orphan drugs are protected by additional exclusivity rights to the pharmaceutical companies, unlike non-orphan drugs. Orphan drugs are awarded a seven- year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE). In contrast, non-orphan entities are awarded five years of exclusivity upon approval, which means that orphan drugs receive two years of additional protection if the orphan indication is awarded upon approval (Reuters 8). Moreover, to further encourage orphan drug R&D by the pharmaceutical industry, the FDA waives certain fees and

costs, provides clinical tax incentives, and assists with protocol during the drug’s clinical trials (Pollack 1990). This is particularly of great importance because it is very difficult to find a large group of people needed for clinical trials to test orphan drugs. These advantages are rarely seen in non-orphan drug development and as a result, many big pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Genentech are seeing them as a “low-hanging fruit” in an unsaturated market.

A specific example of orphan drug development that has shown significant success is the development of Rituxan by Genentech, which has been approved by the FDA for use since 1997. Rituxan was originally developed to combat an orphan disease called lymphocytic leukemia (Dotan 2012). It is an antibody that recognizes a protein called CD20 found primarily on the surface of B cells, and can essentially destroy them. Now it is often used to treat diseases with an excessive number of B cells, overactive B cells, or dysfunctional B cells. Since the development and commercialization of Rituxan, patients’ lives have dramatically improved and Genentech has earned immense profits from marketing the drug (Reuters 6).

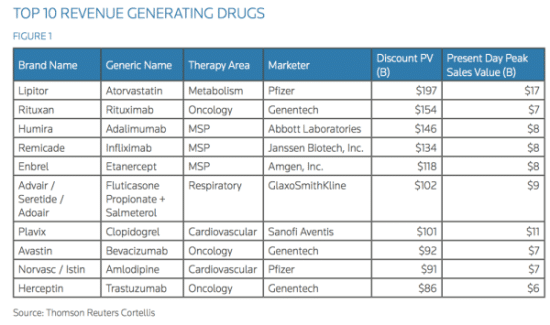

There is yet another advantage for patients and pharmaceutical companies to use orphan drugs, known as off-label drug use. When a drug is FDA-approved to treat one type of cancer but is prescribed to treat another, the drug is said to be used off-label. Dr. Schlechter explains that when a doctor finds an individual with a condition never seen before, or with multiple diseases, off-label drug prescription is the only route to go. Rituxan, originally meant to treat a type of leukemia, is used today to treat a vast array of diseases like multiple myeloma, autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. It is even used to suppress immune rejection after an organ transplant. This versatile use of a drug primarily developed to treat a population of under 200,000 patients is now estimated to treat more than 40 million patients worldwide, thus it is placed on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of essential medicines for basic health systems. Rituxan is also second on the list of top 10 generated drugs in the United States. Genentech has made a whopping $17 billion from Rituxan sales, which is quite astonishing considering the original intended target of the drug.

Rituxan, a drug developed initially for an orphan disease, is second on the list.

Now that we have looked at the huge potential that orphan drugs can have not only on the target crowd of patients, but also on others that were not primarily included, we can safely say that orphan drug development is a key player in the treatment of many diseases worldwide. Next, we can turn our heads to an outlook of the future on orphan diseases and the pathway from bench research to drug approval. At last, we can take a closer look at the people who, with their extraordinary vision, have helped turn these drugs from dreams to reality. Dr. David Zagzag, professor of pathology at NYU Langone Medical Center, has devoted his entire professional life to the research and investigation of a rare genetic orphan disease called “von Hippel-Lindau” disease (VHL). Loss of the VHL tumor suppressor gene is known to contribute to the initiation and progression of some of the most aggressive and resistant tumors through a dysfunctional von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL). These tumors include hemangioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic cysts, endolymphatic sac tumor, pheochromocytoma, bilateral papillary cystadenomas of the epididymis (men) or broad ligament of the uterus (women), and many more. Dr. Zagzag has made a remarkable discovery in the pathway of a key protein called HIF1α, which plays a pivotal role in cancer proliferation and division together with pVHL. At normal oxygen conditions in the central nervous system, HIF1α is marked for degradation by pVHL. In low oxygen conditions or in cases of VHL disease where the VHL gene is mutated, pVHL does not bind to HIF1α. Without the binding of pVHL to HIF1α, HIF1α escapes degradation and is overexpressed. As a result, when HIF1α is overexpressed, it turns on certain genes that help cancerous cells survive and divide in low oxygen conditions and prepare for oncogenesis. This explains why diseases such as hemangioblastomas, clear cell renal carcinomas, and pheochromocytomas are all related: they are all pVHL defective tumors (Zagzag et al. 2005). Dr. Zagzag has paved the way for a brighter future for patients affected with VHL. With remarkable discoveries such as those made by Dr. Zagzag, pharmaceutical companies will continue to draw their attention to orphan diseases and their drug development.

Although the government and the pharmaceutical industry initially neglected the presence of orphan diseases and could not see the potential benefit of treating patients with newly developed drugs, we are now starting to see a change of action. Those affected by orphan diseases are starting to receive more attention from governmental organizations. Pharmaceutical companies will begin to turn to the market of orphan drugs for profit, and researchers like Dr. Zagzag continue to investigate the behaviors of these diseases. The future of patients diagnosed with orphan diseases now looks brighter than ever before, and the search for the panacea to these diseases is closer than ever.

Special thanks to Drs. David Zagzag and Dr. Alan Schlechter for their help, guidance and support throughout the writing of this piece. Without their great insight and unique outlook on the topic I would have not been able to write about this topic.