by Mark Robles-Long

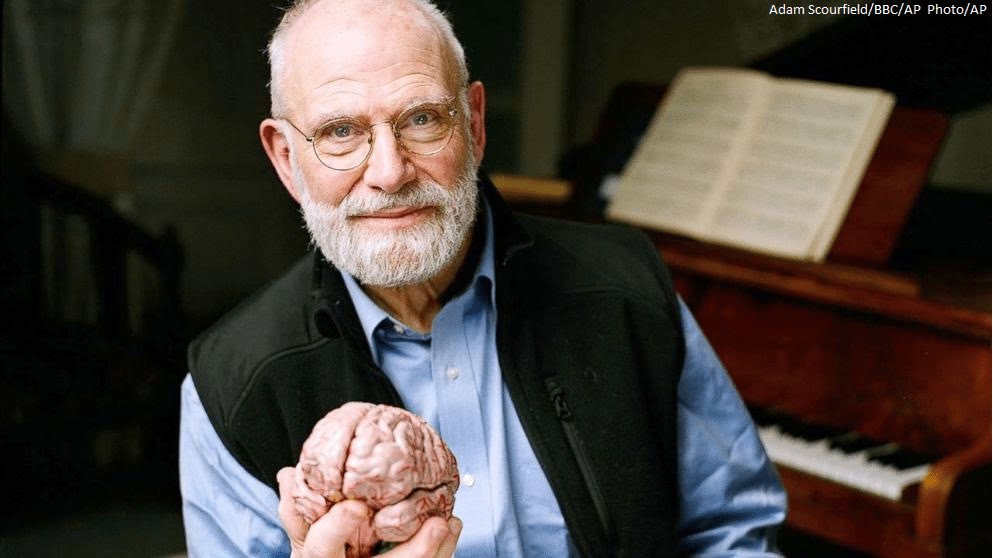

Dr. Oliver Sacks contributed to the field of neurology what often seems to be lacking in other domains of science, medicine, and academia–meditation. Sacks was interested in the implications of mental disorders as they related to the soul and mind rather than just the body. Being not only a pragmatic physician but also a man enthralled by the visceral human experience, he was a type of hybrid thinker who, in one instance, thought of Tourette’s syndrome as both a debilitating disease as well as a source of insight. This was discussed in detail in the popular The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales. Tourette’s syndrome was one disease in which Sacks developed an enduring interest, devoting significant attention to the benefits of a “disease of excess.” Sacks’ books, numbering more than fifteen in total, comprise a sort of encyclopedic diary, logging his experiences and endeavors as he matured into the neurological pioneer and “poet laureate of contemporary medicine” he is remembered as today. In his book Awakenings, an account of one of his most memorable and critically acclaimed experiences, Sacks worked with patients at Beth Abraham Hospital who suffered the residual effects of the disease encephalitis lethargica. In an effort to help those stuck in a catatonic state, Sacks administered L-Dopa, a drug believed to be a remedy for Parkinson’s. While he observed what would be deemed a clinical success from L-Dopa, with patients rising up from their previously stone-like states and walking or talking for the first time in years, he nevertheless observed a grim reality: even some for whom the drug worked were “awakened” to live a life they did not understand to be their own.

Not knowing this new life and unwilling or unable to adjust, some wished to return to their static state. In addition to encounters with Tourette’s and the case at Beth Abraham, which are but two of his many undertakings, one of Sacks’ most inspiring pieces lies in “The World of the Simple”, the last of the four parts in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. In this, Sacks explains each patient in terms of the gifts with which they were endowed as a result of their conditions, which ranged from Parkinson’s to retardation and Autism. A patient by the name of Rebecca evoked a sort of realization in Sacks while he worked with her: that his and his colleagues’ focus was inadequate, directed toward the obvious deficits rather than the implicit powers caused by disorders like Rebecca’s and those with similar conditions. Oliver Sacks used writing as a medium by which he could transcend the density of empirical, scientific papers and reach those looking for a meditation upon the human brain as it related to the human condition.

Considered to be one of, if not the most, extraordinary of Sacks’ books, Sacks presented The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat as a collection of case studies, detailing the condition of each patient, explaining their symptoms and even providing diagnoses; however, following each case was a “postscript” much different than any discussion found in a typical scientific paper, concerned rather with reflection and meditation than a conclusive end argument. This book in particular grabbed the attention of the scientifically adept as well as the common reader, piquing one’s brain as much as their sentiment. In the part titled “Excesses”, Sacks recounted ‘Witty Ticcy Ray’. Ray was a man affected by Tourette’s syndrome, a disease of neurotransmission that did not gain popular recognition by researchers or the public until seven years after Sacks first met Ray in 1971.1 Sacks described Tourette’s as emerging from disorders of dopamine and the primal brain responsible for the fundamental aspects of personality and affect: the basal ganglia and amygdala. Nearly four and a half decades later, Sacks’ description is consistent with the believed causes of Tourette’s today, what the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes calls abnormalities of the basal ganglia, frontal lobe and their interconnections, as well as deleterious changes to the states and courses of neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine.4 As a result of this complex neurological disorder, Sacks believed there existed a gap between the body and the mind; however, he also argued that the disease simultaneously acted to enhance the afflicted person’s experience of the world. Sacks often looked for and found these dual effects of disorders. Ray, although nearly incapacitated by violent tics, sublimated his disturbances into music.

“He was (like many Touretters) remarkably musical, and could scarcely have survived–emotionally or economically– had he not been a weekend jazz drummer of real virtuosity, famous for his sudden and will extemporisations, which would arise from a tic or a compulsive hitting of a drum and would instantly be made the nucleus of a wild and wonderful improvisation, so that the ‘sudden intruder’ would be turned to brilliant advantage.”

This redirection of excess nervous energy was necessary for Ray to live a life considered normal. Even if it was for just a few numbers on stage, Ray, like many others of Sacks’ patients, was able to take back some semblance of autonomy. Though not mentioned in this book as Ray was, another of Sacks’ Tourette’s patients and friends, Shane, had a similar method of channeling energy. Whether practicing karate, making art, or horseback riding, Shane appeared nearly tic-less; his symptoms were suppressed while his mind and body were allotted peace. However, this guise of normality did not last. During a lull in his martial arts practice, Shane would feel forced to flail his head, buckle his knees, and stretch his with Shane through a botanical garden, remarked about Shane’s propensity for touch.This remark, as were many of Sacks’, fell nothing short of admiration for Shane’s tactile curiosity and “careful testing of the limits of the forbidden.”5 Through use of his hand as a main sensory organ, Sacks believed Shane knew not merely just the sight and sound of his environment as might every other normal person, but also the feel and touch. In his encounters with both Ray and Shane, Oliver Sacks commented on the drug Haldol, a tranquilizer that when administered in small doses, acts to contain tics. This drug enabled patients to regain control over their bodies; at least, so it appeared. After enduring tics that were simply slowed down and extended as a result of taking Haldol, assuming almost catatonic positions, Ray expressed an idea to Sacks about the inadequate restorative power of the drug, asking, “Suppose you could take away the tics…What would be left? I consist of tics–there is nothing else.”1 It was clear to Sacks that synthetic treatment did not give these individuals what natural remedies such as music or painting did: a new health and “resilience of spirit.”

Haldol was not the first drug Sacks found to be less than ideal. Nearly 30 years before Shane but only two years before Ray, Sacks took to treating a group of patients at Bethlehem Abraham Hospital in The Bronx in New York City. Suffering from encephalitis lethargica, these patients were survivors of the 1920’s epidemic of the disease more commonly known as “sleepy sickness.” They were placed in the care of Sacks who had just finished residency at UCSF Medical Center’s Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco one-year prior. Believed to be a result of an extreme immune reaction to a bacterial infection, this disease affected neurons of the basal ganglia and midbrain as well as levels of dopamine in the nervous system.6 Oliver Sacks operated on this theory, focusing particularly on the similarity of dopamine deficiency between this disease and Parkinson’s.

“In 1969, I gave these sleepy-sickness or post-encephalitic patients L-Dopa, a precursor of the transmitter dopamine, which was greatly lowered in their brains. They were transformed by it. First they were ‘awakened’ from stupor to health: then they were driven towards the other pole–of tics and frenzy.”

These postencephalatic patients experienced side effects of the drug, ranging from relatively benign exaggerated movements of the appendages and repetitive speech or movement to what appeared as an explosion of primal urges– insatiable appetites for sex and food. Although one individual did not experience the latter, she was awoken to a “television age” at the age of 64 and within 10 days, her unwillingness or her inability to release the delusion that it was still 1926 and that she was still 21 resulted in her non-responsiveness to L-Dopa. Some patients, however, were able to use the drug to their advantage in spite of its side effects. One woman’s inclination to repeat her words, an effect of L-Dopa, disappeared when reading a book or singing;7 another’s instability was given order when he returned to work as a cobbler.8 In large similarity to the Tourette’s patients, those at Beth Abraham found consolation in unique ways. In both cases as in many in the medical field, pharmaceuticals affect individuals differently–positively, negatively, or not at all.

“Haldol can be an answer to Tourette’s, but neither it nor any other drug can be the answer, any more than L-Dopa is the answer to Parkinsonism. Complementary to any purely medicinal, or medical, approach there must also be an ‘existential’ approach: in particular, a sensitive understanding of action, art and play as being in essence healthy and free, and thus antagonistic to crude drives and impulsions, to ’the blind force of the ‘subcortex’ from which these patients suffer.”

While a clinical procedure is nonetheless necessary in any medical setting. Sacks explains that it is insufficient. This belief is evident that his own approach to neurology wherein he balances his medical expertise with a unique existential consideration. In other words, his role as a physician was complemented by his ability to write about his patients. In this way, he presented them as complex models of the human condition.

Oliver Sacks’ work with the autistic and cognitively impaired exemplified his capacity to think creatively as well as critically. Autism is one of the most complex neurological disorders today; very little is understood about its causes and mechanisms. The vast amount of symptoms has necessitated a spectrum of the disease known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to be created.9 Oliver Sacks wrote extensively about his encounters with these “simple” individuals noting their deviations from normality in a new light, paying attention to what the disease endowed them with as opposed to what it took away from them. Rebecca, an individual whose disorder was not explicitly mentioned but would most likely lie on the spectrum today, was one of Sacks’ most remarkable patients. Rebecca was wholly simple, as Sacks initially described her: clumsy, moronic, and a “mass of sensorimotor impairments.”1 This state of idiocy, however, did not depict Rebecca in her entirety. Once Rebecca was no longer seen in a clinical setting but instead in the outdoors, on a bench, alone and “gazing at the April foliage”, she appeared, to an astounded Sacks, well and composed.

“Why was she so decomposed before, how could she be so recomposed now? I had the strongest feeling of two wholly different modes of thought,

or of organisation, or of being. The first schematic–pattern-seeing, problem-solving–this is what had been tested, and where she had been found so defective, so disastrously wanting. But the tests had given no inkling of anything but the deficits, of anything, so to speak, beyond her deficits…they had given me no intimation of her inner world, which clearly was composed and coherent.”

Sacks believed Rebecca was inadequately represented. She was regarded as simple because that is how she appeared in a test situation where only neurological vision, as he would term it, was employed. Oliver Sacks aimed to avoid exclusive use of this “lens,” maintaining a delicate balance between neurological and “human vision,” a reiteration of the existential approach.1 Rebecca made clear to him the shortcomings of traditional approaches to the mentally ill. While this approach was not by any means cursory, it lacked what Sacks believe to be a meditative dimension necessary for proper diagnosis, treatment, and portrayal of the individual.

Oliver Sacks considered his patients to be models of the human experience–variable, unpredictable, and peculiar in each case. To him, the quantifiable, testable brain reflected the intricacy of the mind, an abstraction that oftentimes leaves too much room for subjectivity and romanticizing. Exploitation of his patients and idealizations of their conditions were recurring critiques of Sacks; his poetic tendencies were believed to interfere with and exaggerate his empirical findings. 10 While it is true Sacks made claims that at times seemed more likely to appear in a creative piece, his writings were a kind of medical ekphrasis, with his patients as the works of art by which he was inspired. Through this perspective, Oliver Sacks was a progressive neurologist who expanded the field’s focuses, creating a body of work that introduced not only science to creative literature, but also poetry to medicine.