Leah Alexander

Imagine waking up one day to the belief that you are dead, that the life you are currently in is the “afterlife,” and that all your loved ones, who are still with you, are dead as well. This scenario seems like something straight out of a horror movie; however, for Esmé Weijun Wang, a sufferer of Cotard’s Syndrome, this situation was her reality.

A Washington Post article titled “This Rare Illness Makes People Think They’re Dead,” explains: “For almost two months, Wang suffered from Cotard’s syndrome, in which patients think they are dead or somehow nonexistent. Any attempts to point out evidence to the contrary — they are talking, walking around, using the bathroom — are explained away” (Kim 2015). Essentially, Wang was engulfed by the delusion that she was dead, despite the fact that she was still very much alive. Her husband, and others who saw Wang acting this way, tried to talk her out of her dream-like state, but to no avail; Wang was stuck in a world of her own (Kim 2014).

Cotard’s Syndrome, also known as “Cotard’s Delusion” or “Walking Dead Syndrome,” is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder in which one denies his or her own existence to the extent that one experiences the delusion of being dead (Grover 2014). Quite often, this disorder appears alongside other more common psychiatric disorders, such as mood disorders—most commonly, depression and schizophrenia Cotard’s Syndrome has also been found to be associated with self-harming behaviors (Nejad 2012). Moreover, the symptoms of Cotard’s Syndrome are often quite nihilistic, causing patients—who believe they are dead—to feel that their lives were essentially meaningless.Patients with Cotard’s Syndrome described feeling sentiments of “anxious melancholy, ideas of damnation or possession, a tendency for self-mutilation or suicide, hypochondriac ideas about the non-existence or destruction of inner organs or the whole body, and the idea that one cannot die”. Furthermore, patients with Cotard’s have also been found to have a wide array of depressive symptoms, including “the patients’ denial of the world’s existence, the plea to be buried because the patients believe they are a rotting corpse, the conviction that their bowels and stomach are lacking or that even most parts of their body do not work” (Reif 2003). Seemingly, in these most extreme cases, the delusion of being dead is so extreme that the patient not only considers their “soul” as dead but considers their body as dead as well.

As a sufferer of Cotard’s Syndrome, Wang had experienced most of the characteristic symptoms, along with another common symptom of Cotard’s: the inability to feel emotion. In her essay, “Perdition Days,” Wang writes: “I was doomed to wander forever in a world that was not mine, in a body that was not mine; I was doomed to be surrounded by creatures and so-called people that mimicked the lovely world that I’d once known, but . . . could evoke no emotion in me” (Wang 2014). Like most sufferers of Cotard’s Syndrome, Wang could not feel an emotional response to aspects of life that are typically expected to evoke some sort of an emotional response from an individual, like feeling bliss while outside on a warm spring day or anger while being stuck in traffic. Because of this lack of emotion experienced by patients, Cotard’s has often been associated with a similar disorder, known as Capgras Syndrome. Those with Capgras Delusion often express feeling no emotion when shown photographs of their loved ones, similar to the lack of emotion felt by patients with Cotard’s (Kim 2015). Capgras Delusion is very similar to Cotard’s Syndrome, with one of the only differences being that, with Capgras, the affected individual believes that their loved ones are, essentially, “dead” and have been replaced by “doubles,” whereas, with Cotard’s, the affected person believes that him or herself is dead (Wang 2014). Furthermore, it has been found that these disorders share similar mechanisms and arise from a notable cognitive dissonance—or, more simply, discomfort arising from the patient’s newfound idea that he or she is dead—which causes the patient to feel a significant strangeness about the external world, as well as about his or her own body. This feeling is often referred to as “derealization” or “depersonalization” (Debruyne 2009).

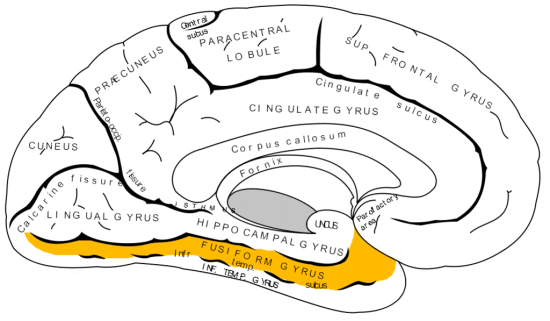

Fig. 1. Neural misfiring in the fusiform gyrus might be a cause of Cotard’s Syndrome (Pearn 2002)

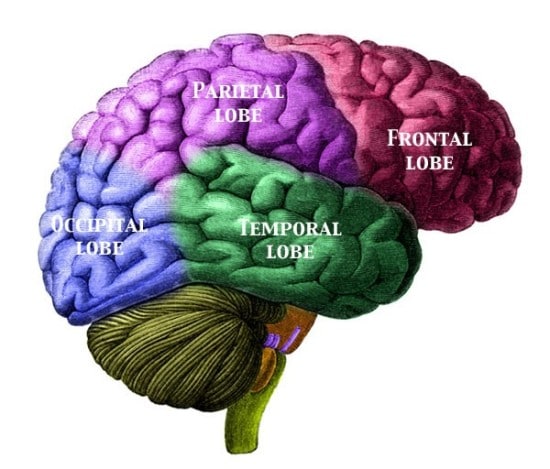

So what exactly causes this zombie-like disorder? Similar to Capgras Syndrome, Cotard’s Syndrome is thought to be associated with neural misfiring in the fusiform gyrus, which is responsible for facial recognition, and in the amygdala, which is responsible for the association of emotions to a recognized face (Fig. 1) (Pearn 2002). Accordingly, this neural misfiring creates a sense of unfamiliarity, in which the patient feels as though the face that he or she is observing is not the face of the person to whom it actually belongs.The face of a person that would normally be recognized by the patient suddenly lacks the familiarity that used to be associated with it. For example, a patient could see his or her own mother’s face and not even recognize her. This lack of recognition ultimately causes the patient to feel a sense of derealization or disassociation from the environment. Furthermore, medical literature suggests that the various symptoms brought about by this disorder is associated with natural lesions in the parietal lobe of the brain (Fig. 2). Because of such lesions, patients will often display more brain atrophy, particularly in the median frontal lobe—than would individuals in control groups (Joseph & O’Leary 1986).

Fig. 2. Natural lesions in the parietal lobe are believed to be a possible cause of Cotard’s syndrome (Joseph & O’Leary 1986)

Cotard’s Syndrome has also been found to be a result of a patient’s adverse physiological reaction to drugs prescribed to patients with impaired renal function, such as Aciclovir and its prodrug precursor, Valaciclovir (Hellden 2007). In this case, patients with kidney disorders would take Aciclovir in order to prevent renal failure but would ultimately experience Cotard’s Syndrome as a side effect. In these patients, the occurrence of the symptoms of Cotard’s Syndrome was affiliated with a high serum-concentration of 9-Carboxymethylguanine (CMMG), the principal metabolite of Aciclovir. With a high serum-concentration of CMMG, the patients with impaired renal function continued risking the occurrence of delusional symptoms, despite the reduction in the dose of Aciclovir (Hellden 2007). Ultimately, however, hemodialysis resolved the patients’ delusions—namely, those that involved the patient’s “negating of the self”—within hours of treatment (Fig. 3). The fact that hemodialysis cured the patient of his or her symptoms suggests that their occurrence might not necessarily be cause for psychiatric hospitalization of the patient.

Fig. 3. Serum concentrations of acyclovir and 9-carboxymethylguanine (CMMG) in relation to neuropsychiatric symptoms of Cotard’s symptoms (Hellden 2007)

Currently, besides the cessation of Valaciclovir as a cure for Cotard’s Syndrome in patients with impaired renal function, there are other available treatments that offer some hope for individuals who suffer from Cotard’s Syndrome. For example, Debruyne et. Al. reports successful treatment of Cotard’s with mono-therapeutic and multi-therapeutic pharmacological treatments, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood-stabilizing drugs. However, the effects of various treatments depend on the specific circumstances surrounding each individual patient. For example, electroconvulsive therapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy for depressed patients who also suffer from symptoms of Cotard’s (Debruyne 2009).

Ultimately, although some information regarding the pathophysiology and treatment of Cotard’s Syndrome is known, there is still a lot to be discovered. For example, after being cured of the significant neuropsychiatric symptoms of Cotard’s, Esmé Weijun Wang reported feeling fatigue, weakness, insomnia, and joint pain. Although she was cured of her delusions and able to feel a full spectrum of emotions, she still felt some degree of physical pain (Kim 2015). The fact that several patients have reported similar after-effects yet little is known of what is causing or how to successfully treat them showing that there is still much to be discovered about this unusual neuropsychiatric phenomenon.