by Sameer Khan

Illustration: ‘D(diagnosis)SM’ by Leana King

Cancer is a debilitating disease— its progression and treatment can shut down entire body systems and leave one unable to perform basic tasks. Emotionally, it makes patients lose their sense of self, abandon important relationships, and destroy their will to survive. Despite the in-depth research conducted to develop cancer drug therapies, the medical field has seen poor results in the improvement of patients’ emotional wellbeing. Psycho-oncology, a field that has emerged very recently, aims to treat patients not solely with drugs, but also with increased attention paid to individualized patient care. This field explores ways to teach family members, friends, fellow physicians, and healthcare staff how to properly approach this dreadful disease.

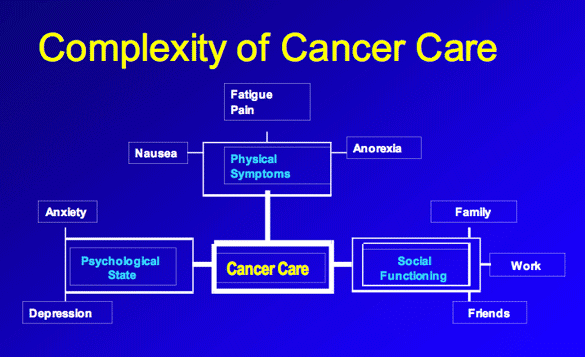

Figure 1: Complexity of Cancer Care. (Chau 2007).

A patient’s quality of life is an aspect of medicine that is often overlooked, especially in the rush to treat a quickly growing tumor. Psycho-oncology emphasizes the importance of patient counseling, anti-depressants and anti-anxieties, family support, and support groups. Unfortunately, cancer patients do not have access to the mental health care they may need. The stigma associated with this care can also leads to embarrassment or anxiety concerning the psychological treatment they receive. In a recent study regarding the effectiveness of support groups in breast cancer survivors, there was “a significant reduction in loneliness scores, promotion in total hope and enhancement in quality of life from pre- to post-intervention”.9 Though these support groups are proven to be beneficial, many people avoid them because they run the risk of interacting with sicker patients and developing anxiety about the future of their own disease. Sometimes, they may also look upon the health of other patients and feel jealous of their wellbeing. Dr. Jimmie Holland mentions in her book, The Human Side of Cancer, that “The sense of being different and ostracized is real, but the camaraderie of the group helps offset it”.4 Despite possible setbacks, support groups can often work to quell patients’ loneliness and provide a sense of solidarity that was otherwise lacking.

Figure 2: Cancer Support Group Meeting. (CSCGM).

Even when patients feel comfortable talking about their disease, they typically still feel a loss of control, both in regards to their disease progression and their decisions with respect to treatment. Cancer patients can sometimes feel left out because the task of decision-making is often delegated to families. In essence, it is difficult to realize that while everybody they know is talking about their disease, they themselves feel as though they have no opportunity to contribute their own input. In another study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, young patients were studied to determine the method of control they felt most comfortable with: physician’s control, patient’s control, or shared control.5 It was found that when there was no clear course of treatment, patients preferred that the physician take full control of their medical journey. Patients longed for a sense of control that could help improve the outlook of the prognosis and boost the confidence they did or did not have. For example, some wanted to know or have tangible proof that their chemotherapy will be able to cure them in some way. Being an active member in this process puts them at relative ease and could prepare them to battle the cancer they face. During such trying times, hope cannot be compromised; efficient and effective communication between the physician and patient is necessary for a positive outcome both psychologically and medically.

This effective communication can be achieved if the patient’s support network considers the type of cancer the patient is fighting. Dr. Jimmie Holland further discusses the specific needs that patients require in every cancer subtype. For example, men with prostate cancer should seek out sexual counselors to deal with irremediable flaccidity, while women with breast cancer require a different type of counseling related to hair loss and recovery from mastectomy. She writes that “treatment for breast cancer is an assault on femininity”, indicating the importance of tailoring mental health treatment and support groups to specific patient demographics.5 It is important to acknowledge how vulnerable patients can feel as they address a potential need for psychological treatment at a time in their lives where they feel most unstable. “Customizing” psychological treatment will help ensure that patients feel safer and more comfortable. This way, the treatments they receive will be most effective as they adopt a positive mindset that will allow them to overcome the medical and psychological obstacles they face.

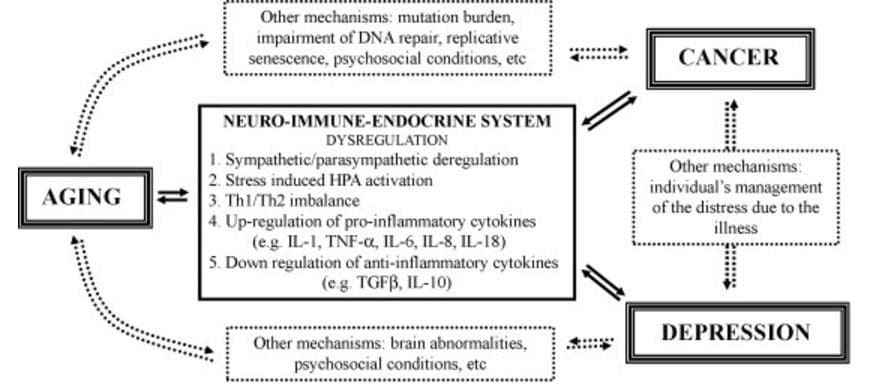

Often because of the isolation felt throughout the course of treatment, patients fall into depression or are plagued with anxiety about the future. Dr. Holland includes a list of drugs a doctor can recommend to their patient to treat conditions such as depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.4 It is imperative that a patient discusses these feelings and symptoms with a psychiatrist because coming to terms with his or her own emotions can positively influence the treatment course. The stigma against using such drugs can be resolved in support groups, where many patients have had positive experiences. Medically, it could be of use to talk to a psychiatrist concerning these issues, but support groups can also function to help patients through difficult changes in psychological state.

Figure 3: Various Psychological Ways that Cancer Can Lead to Depression. (Depression and Cancer).

The best way to avoid these psychological problems altogether though would be to attempt to prevent the cancer in the first place. Cancer screenings have become increasingly common, and studies were conducted to assess the differences in education level and socioeconomic status of patients who received screening tests for cancer and those who did not. A study of colorectal cancer showed that patients of lower socioeconomic backgrounds and less education were less likely to show up for screenings than university graduates.8 This finding can be due to the distrust for the healthcare field that many underserved communities harbor. Trying to find ways to make care more affordable and transparent will help provide incentive for people to get tested. In addition, primary care physicians should urge patients to obtain screenings both regularly and whenever symptoms are present.

If the cancer cannot be prevented and gets to a point where it is difficult to control, what course of action do the family, patient, and physician take? What decisions should they make? These questions are difficult to ask because they can lead to the topic of death and euthanasia. Does the patient want to be kept alive by the numerous drugs he or she is consuming for only a few extra months? Or do they wish to abandon the medications, resolve the issues in their lives now, and continue to lead a fulfilling life while they still can? Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End says “our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged is the failure to recognize that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer; that the chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life”.3 He acknowledges the notion that people have the agency to construct their own stories. Leaving the world without writing an appropriate proper ending can leave one with deep, irreconcilable regret. A psycho-oncologist should be able to guide a patient as he or she confronts these questions and determine how the demands of a patient can be fulfilled with his or her best interests in mind. It is this fine line between choosing and rejecting treatment that makes this disease so complicated. This balancing act should be performed by everyone involved in the diagnosis, not by the patient alone.

Works Cited:

1. Chau D. Complexity of Cancer Care.; 2007. Available at: http://www.obgyn.net/articles/supportive-care-more-just-treating-cancer/page/0/6. Accessed October 9, 2016.

2. Depression and Cancer.; n.d. Available at: http://4li.co/depression-cancer/. Accessed October 9, 2016.

3. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York: Metropolitan; 2014.

4. Holland JC, Lewis S. The Human Side of Cancer: Living with Hope, Coping with Uncertainty. New York: HarperCollins; 2000.

5. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al. Cancer Patients’ Roles in Treatment Decisions: Do Characteristics of the Decision Influence Roles? J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(28):4364-70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8870.

6. Monthly Program-Specific Networking Groups.; n.d. Available at: http://cancersupportcommunitymiami.org/monthly.htm. Accessed October 9, 2016.

7. Seror V, Cortaredona S, Bouhnik AD, et al. Young Breast Cancer Patients’ Involvement in Treatment Decisions: The Major Role Played by Decision-making about Surgery. Psychooncology. 2013; 22(11):2546-56. doi: 10.1002/pon.3316.

8. Smith SG, McGregor LM, Raine R, Wardle J, Von Wagner C, Robb KA. Inequalities in Cancer Screening Participation: Examining Differences in Perceived Benefits and Barriers. Psychooncology. 2016; 25(10):1168-1174. doi: 10.1002/pon.4195.

9. Tabrizi FM, Radfar M, Taei Z. Effects of Supportive-expressive Discussion Groups on Loneliness, Hope and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Control Trial. Psychooncology. 2016; 25(9):1057-63. doi: 10.1002/pon.4169.